Frequently Asked Questions

There's a lot of questions that come up on our community subreddit (/r/ArtFundamentals) pretty frequently, so with the encouragement of a few community members, I've decided to compile the responses I find myself typing out most often here. If the question you wish to ask isn't answered here, or if you have additional questions related to those here, you may still feel free to ask the community. Just make sure you've gone through this page diligently first.

Questions

-

Conceptual Questions

- Why is this so hard?

- I'm not interested in realism. Why would studying the real world help me?

- I want to learn to draw, but I just can't find the motivation to start.

- How do I draw from my shoulder?

- Can I draw from my elbow instead of my shoulder?

- Can I mix drawing from my shoulder and elbow?

- How should I hold my pen?

- Should I draw with my hand and arm hovering over the table? Can I rest my hand on the page while I draw? Can I rest my elbow on the table while I draw?

- Can I draw lines and ellipses from my wrist if they're really small?

- Is it okay if I do my lessons on the bus, laying on my bed, on the couch, or in other similarly less-than-stable positions?

- Do I need an angled drawing desk or is a flat table okay?

- Why do you want us to use ink/fineliners? Is pencil okay? Is ballpoint pen okay?

- My fineliners keep dying!

-

Common Misconceptions

- If the results of an exercise are not beautiful, I am doing something wrong.

- Drawing from my wrist is easier for me, so I think that's how I should be doing it.

- I want to become a digital artist, so doing the exercises in pen seems useless to me.

- Are you trying to tell me that observational drawing is wrong?

-

Lesson Questions

- How do I know when to move onto the next lesson?

- Do I need to be able to do each exercise perfectly before moving onto the next one?

- Once I'm done with a lesson, should I ever do these exercises again, or am I done forever?

- I can't figure out the rotated boxes and/or organic perspective boxes exercises from lesson 1! Am I doomed to fail?

-

Patreon Supporters

- I love what you're doing here and would like to give something back. How can I do that?

- What do I get for supporting you on patreon? What's the point of pledging $1, or $3, or even more?

- I've pledged on patreon - how do you know which reddit username I'll be using to submit homework?

- Patreon only collects at the first of the month - do I have to wait until then before submitting homework for critique?

- How do I get you to critique my homework? Are there any rules I need to follow?

- I've submitted my homework correctly. How do I know you've seen it?

- How many submissions can I send in per month, and how long must I wait between submissions?

- I've given you money - why do I need to start at lesson 1 if I'm confident I already know that stuff? Can't I just jump straight to the good stuff?

Answers

-

Conceptual Questions

Why is this so hard?

Everything is difficult at first. That doesn't mean it's not meant for us. Walking seems impossible at first, and yet it's one of the abilities that propelled us to dominance.

When we start out, we tend to have a lot of things working against us. We've probably been writing for quite a while, so it's deeply ingrained in us to manipulate pencils and pens from the wrist. As a species, we've developed brains built for pattern recognition, quickly simplifying all processed information and throwing away anything superfluous - great for keeping us alive, not so great for capturing minute detail from observation.

The process of learning to draw is one focused on rewiring and rebuilding. We change the modify the way our brains sees and processes the world, we build up unused muscles in our arms, and we gradually move from using our cerebrum (the frontal cortex, which handles conscious thought and higher functions) to our cerebellum (which manages muscle memory and motor functions). Eventually it becomes second nature.

Biologically speaking, everyone has the cards stacked against them. It's all too common for those who wish to learn how to draw to excuse themselves from the challenge of it by thinking them special. We never truly know our limitations - we only know where we've decided to give up.

I encourage all of you to read the story of Francis Tsai, an artist who did work for Marvel, Dungeons and Dragons, and others. When he turned 42, he was diagnosed with ALS, a disease which eventually robbed him of the ability to use his arms and hands. Personally, that's probably where I'd give up. But he didn't - he started holding an iPhone in his left foot, and drawing with the big toe of his right foot. Eventually, he lost the use of his feet. Again, he was not deterred. He started using gaze tracking technology to draw on a computer. Admittedly, the styles of his drawings certainly changed as he faced these challenges, but the fact is that he did not let them stop him, until passing away in 2015.

I'm not interested in realism. Why would studying the real world help me?

I hear this most often from those interested in drawing cartoons, comics, manga, etc. Ultimately, the answer is simple - almost everything that humans have drawn has been in some way informed by our knowledge of the world around us. Furthermore, everything we draw is in some way derivative of something else. The artists you admire, and who inspire you, themselves are derivative of something else. If you derive your work from theirs alone, yours will always fall short of that target. The way around this is to go as far up the chain of derivation to the very source. That is always, no matter the style, no matter how distant, the real world.

Now that doesn't mean you can't study those artists as well - all it means is that having a solid foundation informed by reality will help you better understand the choices those artists made. Ultimately you don't want to copy blindly - what you're after is understanding, so that you can apply their ideas and techniques to your own work.

I want to learn to draw, but I just can't find the motivation to start.

For this, I'll direct you to the short blurb I wrote On the Subject of Motivation.

How do I draw from my shoulder?

While this is tough to explain, there's an exercise you can perform that might help clarify things.

Start by holding your hand in front of you, as though you were going to draw on a piece of paper. You can even do this while holding a pencil. Holding your arm still, pivot your hand at the wrist, moving it back and forth slowly, familiarizing yourself with how that feels and the range of motion it affords you.

Next, lock your wrist joint. Don't get tense, just consciously stop yourself from performing the action you had just experienced (pivoting from the wrist). Having locked that joint, now try pivoting from your elbow. You should find the range of motion is considerably larger, that you can cover a much greater distance by moving back and forth from that particular joint.

Once you've gotten used to that motion, again, lock your elbow. Now that both the preceding joints are locked, try moving your arm from the shoulder. You'll find that as the shoulder is a ball joint, you won't be limited to hinging back and forth as you were with your elbow - you should be able to move it in multiple dimensions, back and forth, slowly exploring that range of possible motion.

As we are unfamiliar with how our arms can be used, it's normal for the concept of drawing from the shoulder to feel strange and unclear. This exercise can help you become better acquainted with these concepts. Additionally, I find that when first learning to draw from the shoulder, I'd often lose track of things and slip back to drawing from the wrist. Whenever I'd catch myself, I'd quickly go through this exercise to remind myself what it means to draw from the shoulder, before continuing with what I was doing.

Can I draw from my elbow instead of my shoulder?

This is something I often hear, and my first question is generally: Why? The answers range from struggling to draw from the shoulder, to not having enough room, and so on.

I strongly encourage you not to give up on drawing from the shoulder - while drawing from your elbow is something that will be fine once you've gotten fully comfortable with your shoulder, it can be a little dangerous right now, as it sets a bad precedent. Do not make choices based on what is easy and what is difficult, as this will lead you down the path of least resistance, continually avoiding conquering challenges. Instead when you come up against something difficult, put the work and time in to conquer it. Once you're comfortable with going down either path, you are ready to make that decision for yourself.

Can I mix drawing from my shoulder and elbow?

This isn't a great idea - reason being, mixing pivots muddies up the feelings that I mentioned here. Learning to draw from the shoulder is very much about getting acquainted with the particular motions involved, and how they feel. Having distinctly different sensations allows you to detect when you're doing one versus the other - it allows us to catch when we've stopped doing what we intended. By mixing all of them together, we lose this distinction, and end up with far less control over what our arm is doing.

How should I hold my pen?

One thing to keep in mind is that the way you hold your tool is completely specific to that tool. Drawing classes will teach you various ways to hold a pencil that differ considerably from how you might hold it when writing (commonly known as the tripod grip). This is because the pencil has multiple contact surfaces which can make a variety of kinds of marks. By holding our pencil with different grips, we have better access to these dimensions of mark making, giving us the freedom to make our drawings more dynamic. Holding a pencil overhand will allow us to make marks with the side, the tip, and even take advantage of situations where we've exposed a greater length of lead by cutting away the wood of the pencil with a knife.

Now, I encourage the use of fineliners/felt tip pens for most of my lessons. This tool really only has one contact surface - the tip. The variety and dynamism we can achieve with this tool does not come from its different contact surfaces, but rather from controlling the amount of pressure we apply. For this, a tripod grip works quite well, so I always recommend drawing with a fineliner in the same way one would write. Keep in mind though that when starting out, your capacity for pressure control is quite limited. You'll quickly go from nothing to full pressure. This is normal, and with time and practice, your ability to control this use of the tool will improve naturally.

Should I draw with my hand and arm hovering over the table? Can I rest my hand on the page while I draw? Can I rest my elbow on the table while I draw?

Before I give the answer, lets talk about what happens when you rest a part of your arm on the table while drawing. There are both advantages and disadvantages. One significant benefit is that you gain added stability while drawing. On the other side of the coin, resting part of your arm will have an anchoring effect, increasing the amount of resistance you face when moving that arm. This in turn can make it much easier to slip back into drawing from your elbow or your wrist, where the resistance may be diminished.

Now, resting your hand gently and resting your elbow will cause this effect to varying degrees. When asked this question, I will generally state that it's okay to rest your hand gently on the page, but not your elbow. Reason being, resting your elbow will almost completely guarantee that you'll be drawing from your elbow as a pivot instead of your shoulder, as it becomes a very heavy anchor. Resting your hand instead does increase the amount of resistence you encounter as you drag that hand along, but you can still draw from your shoulder while doing so. Just be constantly aware of which pivot you're drawing from and correct yourself whenever you find that you've slipped back to your elbow or wrist.

Can I draw lines and ellipses from my wrist if they're really small?

The pivot you choose - be it wrist or shoulder - does not have anything to do with the size of the marks you're making. Instead, it's about the nature of the mark you want to make.

If you're interested in making a mark that needs to be very stiff and precise - like very minute details in a texture, or if you're writing (letters have very tight twists and sharp turns), pivot from your wrist. This will give you very fine control over your marks. Keep in mind that while you may be thinking, "well obviously I always want to be in control," this is the case far less often than most beginners realize.

The other side of the coin is when you want to make lines that flow smoothly. These lines should be drawn from the shoulder, as the tight control you get from drawing from your wrist will often break the flow you desire. The vast majority of lines you'll be drawing - especially in terms of constructing solid forms and even shapes - require this kind of smooth flow, where they can still be quite successful even if they're slightly off from their intended point.

Is it okay if I do my lessons on the bus, laying on my bed, on the couch, or in other similarly less-than-stable positions?

Probably not a good idea. Anything that keeps you from being in a focused, studious mindset should be avoided. This includes unstable drawing positions, busy/crowded/noisy spaces, messy environments, drawing on lined or graph paper, and so on. You absolutely want to put your best effort into completing the exercises, as that is the way you're going to get the most out of them. Being in a less than optimal mindset will cause you to work sloppier, which is something you want to avoid at all costs.

Do I need an angled drawing desk or is a flat table okay?

Angled drawing surfaces help, but they are by no means required. Just make sure you're able to keep good posture and aren't hunching over.

Why do you want us to use ink/fineliners? Is pencil okay? Is ballpoint pen okay?

I explain this in detail in this article. Some people think that it has to do with being able to undo and erase, and that digital media is cheating - it has nothing to do with those. Similarly to the environment in which you do the exercises, this has a lot more to do with how the tools you use impact your mindset, which in turn influences what you learn.

My fineliners keep dying!

Some brands are better than others. Some are worse. Some individual pens are duds, while others will keep going like champs for a long time to come. Then there's the fact that these lessons require a LOT of drawing, and therefore a lot of ink. You're bound to tear through quite a few of them.

If possible, try to buy your pens in person, as most art supply stores will let you test them out before buying (they often have a strip of paper full of scribbles where others have done the same). Additionally, the angle at which you hold your pen while drawing will impact the ink flow. Holding your pen perpendicular to your page will usually result in the best possible flow of ink.

Lastly, avoid pressing too hard on your pens. This could damage the tip.

-

Common Misconceptions

If the results of an exercise are not beautiful, I am doing something wrong.

This is the farthest from the truth. The fact of the matter is, you're going to make a lot of mistakes. It is from those mistakes, and more importantly reflecting upon them, that we learn and grow.

Try and keep that which is an exercise separate in your mind from that which constitutes a piece of artwork. For the latter, the final result obviously matters, and the means to attain it matter much less so. An exercise on the other hand is all about the process you used, and what you learned from it. The end result could very well be shredded and burned for all it's worth.

Additionally it's important to realize that I'm a sneaky devil, and I'll often include certain exercises that are there with the goal of making you stumble and fall. More accurately, they're there to introduce you to concepts and challenges that you're not yet equipped to face. This is because it's much easier to explain to someone how to tackle something if they've already tried and failed. It also helps to eat a healthy serving of failure now and again, as we must all become comfortable with it. There's a lot of failure in the road ahead of us, and it is not something we should be eager to avoid.

Drawing from my wrist is easier for me, so I think that's how I should be doing it.

Too bad! Just because it's easier doesn't mean it's right. It's only easier because it's what you're familiar with, and given practice, drawing from your shoulder will also be easy. If you choose to only do what is immediately accessible, you will fall into the trap of always going down the path of least resistance, and ultimately never reaching any of your goals. Expect to face a lot of failures on your path. These are not pitfalls, but rather opportunities to reflect, learn and grow.

I want to become a digital artist, so doing the exercises in pen seems useless to me.

In the second half of this article, I explain why it is better to do the exercises using the recommended tools, rather than digital media. That said, the tools you use to learn have nothing to do with the tools you intend to use later on. You're not learning how to use the tool, but the tool you're using will have certain advantages and disadvantages when it comes to teaching you the lessons you do learn. I have chosen 0.5mm fineliners as the required tool for lessons 1-6 because it helps the most in teaching students good habits such as thinking before drawing, an awareness of line economy, dealing with mistakes, pressure control, and so on.

Are you trying to tell me that observational drawing is wrong?

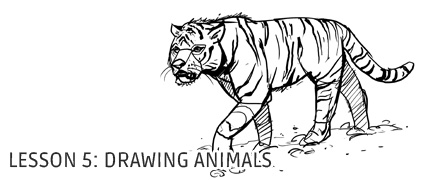

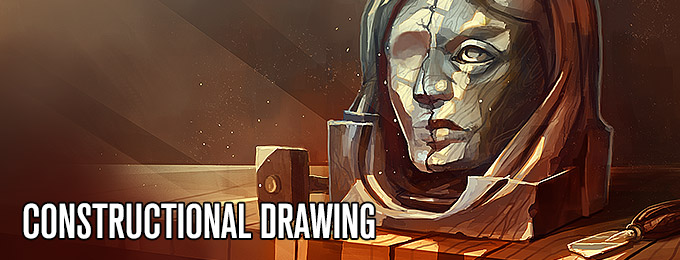

Not in the slightest. This question is posed in relation to the whole constructional drawing vs. observational drawing dichotomy, where most fine arts based drawing classes focus on sketching from observation, while the lessons here focus primarily on construction. That isn't to say that they are mutually exclusive. Not even close.

Both methods of learning/teaching attempt to teach you how to draw. This means learning how to think in 3D space, and also to observe and study the specific details and qualities present in whatever it is you're looking at, so that you can carry it over into your drawing accurately. The difference is that the fine art focuses on observation first and foremost, and hopes that construction will be inferred. In my experience, this is where most people struggle and end up feeling that they lack the talent for it.

Constructional drawing instead focuses on building up simple primitive forms first and foremost as a foundation and structure. Observation is certainly used in order to identify which primitive forms best suit the object being drawn, but it's less about detail, more about seeing through what is present to its very core. From here we learn to break down these primitive forms and building up complexity to establish something solid and tangible before delving into detail.

From there we are free to apply the principles of observational drawing, but only once that main construction is complete. It is still extremely important to learn to look more than you draw, and to refrain from relying on one's (faulty) memory, but the core of constructional drawing is that this detail phase is not what is important.

Ultimately both methods seek to teach you the same thing, but I choose to teach constructional drawing, as it feels like it makes more sense to beginners, and is an easier road for them to take that avoids worries of whether or not talent exists or is a factor at all.

-

Lesson Questions

How do I know when to move onto the next lesson?

Ultimately you don't. For lessons 1 and 2, I do have self critique resources available (through the blue button at the top of each lesson), where you can find common mistakes and pitfalls, but ultimately it is very difficult for someone to determine whether they understand the concepts presented. For this reason, learning in isolation is ill advised. We are all susceptible to misunderstanding key points and carrying on with that misunderstanding until it becomes a big problem.

For this reason, you are all welcome and encouraged to submit your completed lesson homework for a free critique by the /r/ArtFundamentals community on reddit. That community is actually where all of these lessons began, before drawabox ever existed. While I no longer do homework critiques for free, patreon supporters with $3 or more pledged are still eligible to have me review their work. Often times the free critiques are just as good though, as we have some fantastic members in the community who are very helpful. I also try and keep an eye on them to ensure that there aren't any misunderstandings of the material being spread around.

Whether you choose to seek the help of others or not, make sure that you read through the lessons and exercise descriptions carefully. There's a lot of material here, and it's quite dense - so it's normal to require multiple read throughs to pick up on certain things. Additionally, I try to provide as much step-by-step instruction as possible, so make sure you follow those to the letter.

Do I need to be able to do each exercise perfectly before moving onto the next one?

Not at all. As discussed at the beginning of lesson 1, under the "As this is probably your first lesson at Drawabox, read this before moving forward!" heading, your focus should be on completing the required amount of homework to the absolute best of your ability. This means following the instructions to the letter, and reading through all the material multiple times if need be. Keep in mind that I say to the best of your ability. Whether you're fantastic with lots of previous experience, or trying your hand at drawing for the first time, the standard you hold yourself to is a personal one.

This doesn't mean you can rush through everything. Sloppy work is anything but the best of your ability. The point is to push yourself to your limits, to find those limits, and to begin finding the little holes that allow you to push beyond that barrier.

The main goal here is to have you understand the goal of each exercise, rather than to be able to achieve it. You want to be heading in the right direction. Being done with a lesson doesn't mean you're done with the exercises, and it is expected that you will continue practicing them for a good long while to come, continually honing and developing those skills.

Once I'm done with a lesson, should I ever do these exercises again, or am I done forever?

Ha! No way. You're stuck with these things forever. For lessons 1 and 2, once you're done with a lesson, the exercises from it should be added to a pool. Every time you sit down for a drawing session, pick two or three exercises from that pool and do them for 10-15 minutes. This way you'll continue to develop those technical skills, improving your ability to draw smooth and flowing lines, to construct solid boxes, to reinforce the illusion of volume with contour lines, to wrap your head around how forms interact with each other in 3D space, and so on. These are the base level skills, but they're also the skills that will have the greatest impact on your overall ability to draw. Practicing drawing kangaroos will get you really good at kangaroos - practicing your use of the ghosting method to draw smooth, confident lines will improve everything.

I can't figure out the rotated boxes and/or organic perspective boxes exercises from lesson 1! Am I doomed to fail?

Not at all. You'll find that I sometimes add exercises that you aren't entirely equipped to handle just yet. These two exercises are examples of that. While by this point I've roughly explained the theory behind vanishing points, and what the different 1/2/3 point perspective systems represent, I haven't talked much about drawing boxes that are rotated freely in 3D space.

Despite that, I'm asking you to tackle these two advanced challenges. Rest assured, I don't expect you to succeed. Instead, through your attempt you're arming yourself with context and understanding. When I later get into how to go about this sort of challenge, you'll be able to relate those instructions back to this attempt, and will in turn be able to digest that information more easily.

Just be sure to read through the instructions and follow them carefully. The rotated boxes exercise especially includes some rather detailed step-by-step instructions with diagrams, so be sure to read and follow them all. Even if you find yourself flailing, push yourself to complete both exercises in their entirety - don't try halfway and give up.

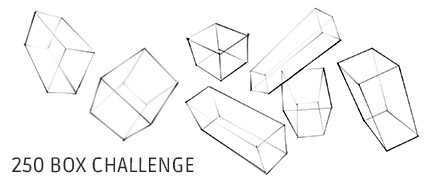

Finally, if you feel that you struggled even slightly with either of these exercises, it would be a great idea to move onto the 250 box challenge next. Be sure to read through all of the notes on that page, and watch both videos. The tip about drawing through your forms is especially helpful, as it should help you better grasp how each box sits in 3D space.

-

Patreon Supporters

I love what you're doing here and would like to give something back. How can I do that?

There's a few ways.

The most impactful way is to the patreon campaign. This is a recurring campaign that sends me the pledged amount at the beginning of every month. Drawing lessons tend to be expensive, and it is through this recurring donation system that I've been able to keep Drawabox going. Instead of asking a handful of people for hundreds of dollars per month (and ultimately helping only them), hundreds of people have been able to pledge very small amounts over longer periods of time, resulting in a much more sustainable source of funding. The way I have always seen it, people can decide however much they feel these resources and services are worth, and pay for them over an extended period of time. At the same time, it also allows those who can't afford to spend very much to benefit as well.

Some people however have wanted to give back, but aren't able to pledge on a month-to-month basis. They have been able to give a lump-sum via paypal, by sending however much they feel they can to [email protected]. Whenever I receive a donation in this manner, I mark the individual down as being eligible for critiques for the month, and send them an email containing all of the patreon-only videos.

What do I get for supporting you on patreon? What's the point of pledging $1, or $3, or even more?

I started out using patreon as a way for people to give back whatever they felt was appropriate - it was really about donating rather than a quid-pro-quo (as all of the lessons are free, as were my homework critiques for the first two years). That premise hasn't changed for the most part, though I have had to implement tiers simply to reduce my workload.

Donating $1 gets you access to additional video recordings of my lesson demos. These aren't anything that special, as they have no audio commentary. The step-by-step breakdown of the process of each one is available for free to everyone as part of the lesson. These are just a token of my gratitude.

Donating $3 or more makes you eligible to have your homework reviewed by me. As mentioned previously, I used to do this for everyone. Eventually demand reached the point where it was no longer feasible (and I was getting completely exhausted), so I implemented a base monthly pledge for this service. While my workload is more manageable now, demand may cause the base pledge to increase again one day, or I may go the route of attaching a certain number of homework submissions per month for different tiers

I don't have any plans of offering more than this for the time being, as I'm still keen on providing as much as I can for free. The rest of this stuff is just here to keep me fairly compensated for the work I put in, and to keep my workload manageable.

I've pledged on patreon - how do you know which reddit username I'll be using to submit homework?

Patreon notifies me by email whenever someone has pledged, so as soon as I see the email notification (which can be a few minutes to a day), I reach out using patreon's messaging system. There's generally two questions that I ask - firstly, if it's alright to list you by your full name or some other alias on the thank you list, and secondly, what your reddit username is.

Not everyone who pledges seeks critiques, and some decide later on that they'd like to partake. Feel free to hold off on creating a reddit account (if you don't already have one), but just be sure to reach out and let me know what your username is before you submit any homework.

Patreon only collects at the first of the month - do I have to wait until then before submitting homework for critique?

Nope! I trust that pledges will be honoured, so I welcome homework submissions immediately after a pledge has been made. While I've had a couple sly foxes cheat me out of a few dollars, the vast majority have held to their word. I don't forsee any problems in continuing this way.

Patreon has more recently introduced a feature where pledges are collected immediately, and then again on the first of the following month. I've decided not to take advantage of this, as it has the potential risk of someone pledging on the 30th and being charged, then being charged again on the 1st. That simply isn't fair, so I'll continue using the honour system until patreon implements a better solution.

How do I get you to critique my homework? Are there any rules I need to follow?

At the top of each lesson, you'll see two yellow/orange buttons. One says Submit Homework for Critique by the Community (free!), and another says Submit Homework for Critique by /u/Uncomfortable ($3+ Patreon Only). If you're supporting me on patreon with a pledge of $3 or more, the second button is the one you want. The first will allow you to submit your homework directly to the subreddit - you aren't guaranteed a response, but so far I haven't seen a single submission not get feedback.

The second button will instead take you directly to a specific reddit post for the given lesson. You can submit your homework there as a comment - be sure to host your homework somewhere (Imgur is what most use, as it does not require an account), and include a link to the album in your comment.

I do treat this as a structured drawing course of sorts, so I am strict in regards to the requirements one must follow:

- Make sure you complete the lesson in its entirety before submitting. Lessons 1 and 2 are split up into 3 sections each - do not submit one section at a time.

- Use the tools recommended in the homework section(s) of the lesson. Lessons 1-6 require the use of a fineliner/felt tip pen, while the requirements for the other lessons vary.

- Don't skip ahead. Complete the lessons in order.

I've submitted my homework correctly. How do I know you've seen it?

When homework is submitted to the correct thread, I get a notification through reddit. Once I see that notification, I add it to my backlog spreadsheet. All of the ones that are greyed out have been critiqued, while the ones at the top have not. I usually critique them in the order they were received, but on occasion I'll strategically critique them out of order if I know I don't particular ones will take me more time than I have.

If your homework is listed on this spreadsheet, then it has been acknowledged and I will get to it eventually. My goal is to critique within 48 hours of submission. Usually I manage under 24 hours, while every now and then circumstances will force me to take longer. If however you don't see your submission on the list within 24 hours of submitting, feel free to message me on reddit. I have let a handful slip through the cracks over the last couple years, though it's also possible that you may have not submitted correctly, leading to my not receiving a notification.

How many submissions can I send in per month, and how long must I wait between submissions?

For now, I leave this up to you. I do however ask that you take into consideration the amount you've pledged per month. My critiques can take anywhere from a few minutes to 20, and in some special cases take me far longer. It really depends on the complexity of what I need to explain. Consider how much time you're asking of me in a given month, the value in the lessons themselves, and what you're giving in return. Decide for yourself what you believe to be fair.

I've given you money - why do I need to start at lesson 1 if I'm confident I already know that stuff? Can't I just jump straight to the good stuff?

Nope. You'll benefit more than you realize from going back to the absolute basics regardless of your perceived skill level, as this helps us to fill in all of the holes in our foundation. I myself went through this stuff after a solid decade of drawing, and I benefitted immensely from it. On top of that however, certain key mistakes are much more noticeable and identifiable in the earlier lessons, whereas later lessons tend to allow us to hide them somewhat. This effectively makes it much more difficult for me to give you valuable critiques.

On top of that, even when lessons 1 and 2 are complete, I still insist that students continue practicing those exercises regularly as warmups. This is because we never truly attain mastery over these basic skills, and with disuse they can get rusty. We need to work towards continually sharpening, and ultimately keeping them sharp.

Articles

Additionally, I've got a handful of articles written on various topics that may answer some questions in greater detail.