At this point, I've been critiquing homework submissions for well over a year, and when you see hundreds of submissions for each lesson, you start to notice patterns in the mistakes people make. Such patterns bring to light holes in certain parts of the lessons. More recently, I've noticed something that is missing across the board, and is core to the approach to drawing that we teach here.

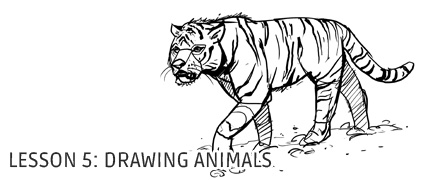

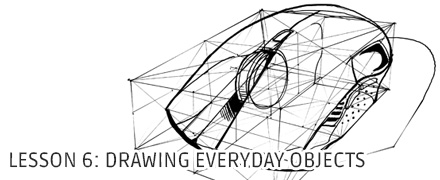

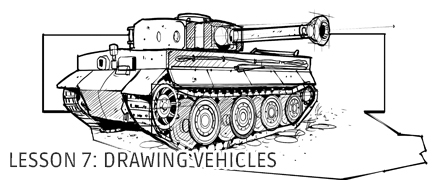

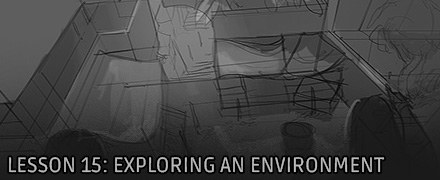

This issue is relevant to many lessons, with a special focus on the dynamic sketching lessons (3-7), so instead of changing each lesson, I'll explain what's missing right here, as a standalone article.

We're going to talk about constructional drawing.

Some of you may be aware of the concepts behind observational drawing, which is what you'll learn from any fine-art oriented drawing class worth its salt. It's the bread and butter of representational art, and it follows a fairly simple process. You look at something, and then you draw what you see. Unfortunately as human beings we are not wired for such a deceptively simple task. Our brains immediately disregard and simplify the vast majority of the information we glean from observation, so our brain only has to deal with the bare minimum. It's a trait we all possess as humans, and it's one we must overcome through practice. Observational drawing is a process that encourages us to stop simplifying the things we see into symbols and icons, and truly see what we see, in all of its complexity and its imperfection.

Unfortunately, when using pure observational drawing, students will generally focus very much on all of the detail unfolding before them, attempting to deal with it all at once. The result generally demonstrates little understanding of how the objects drawn sit in three dimensions, and how things relate to one another spatially. Instead the scene becomes flattened out, understood only in two dimensions. This gets even worse when drawing from a photograph instead of from life - since a photo is already in 2D, it removes any use of spatial skills altogether, and becomes a matter of directly replicating the image in a drawing.

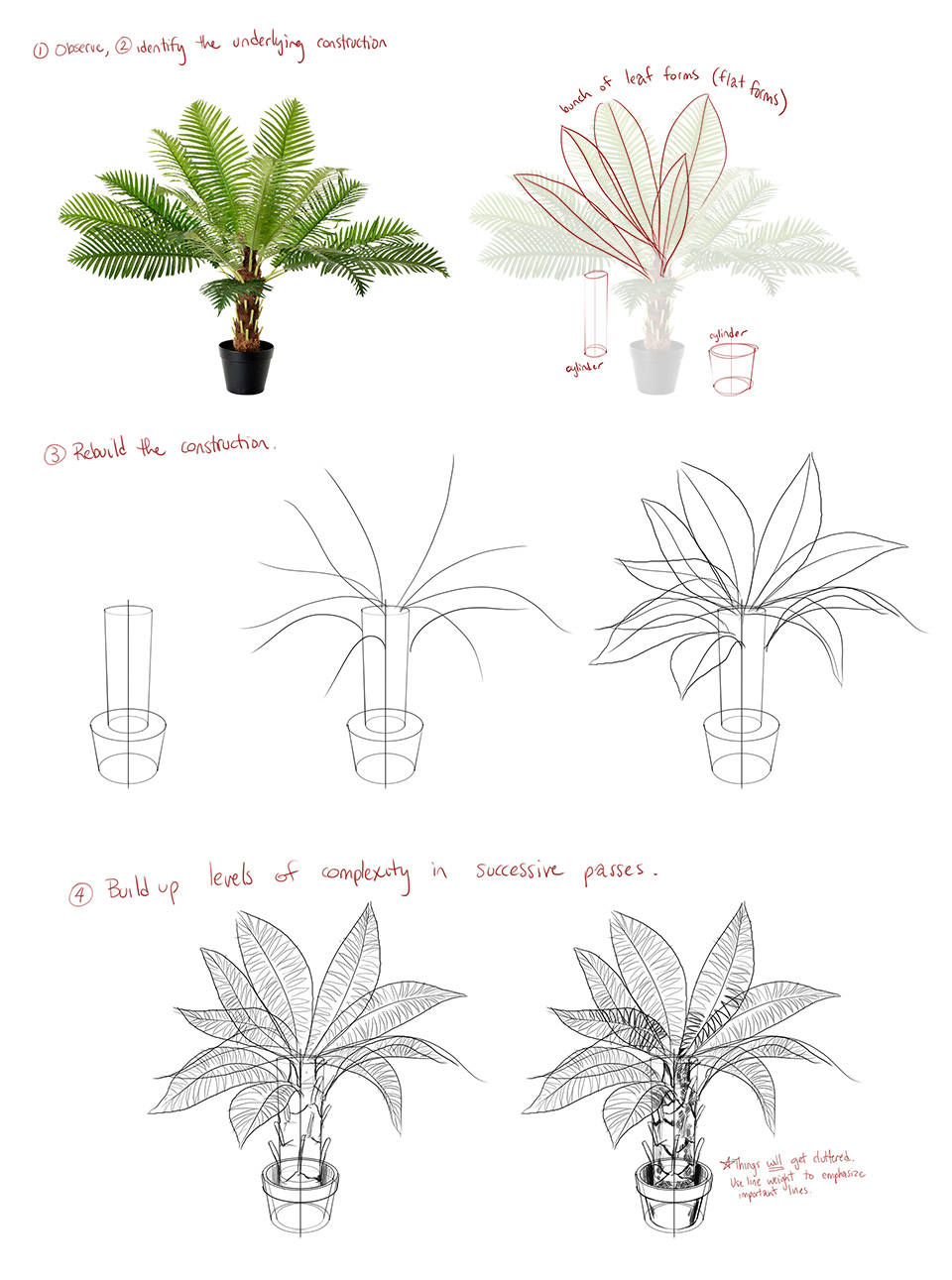

So, instead of pure observational drawing, we use what I like to call constructional drawing. The process is as follows:

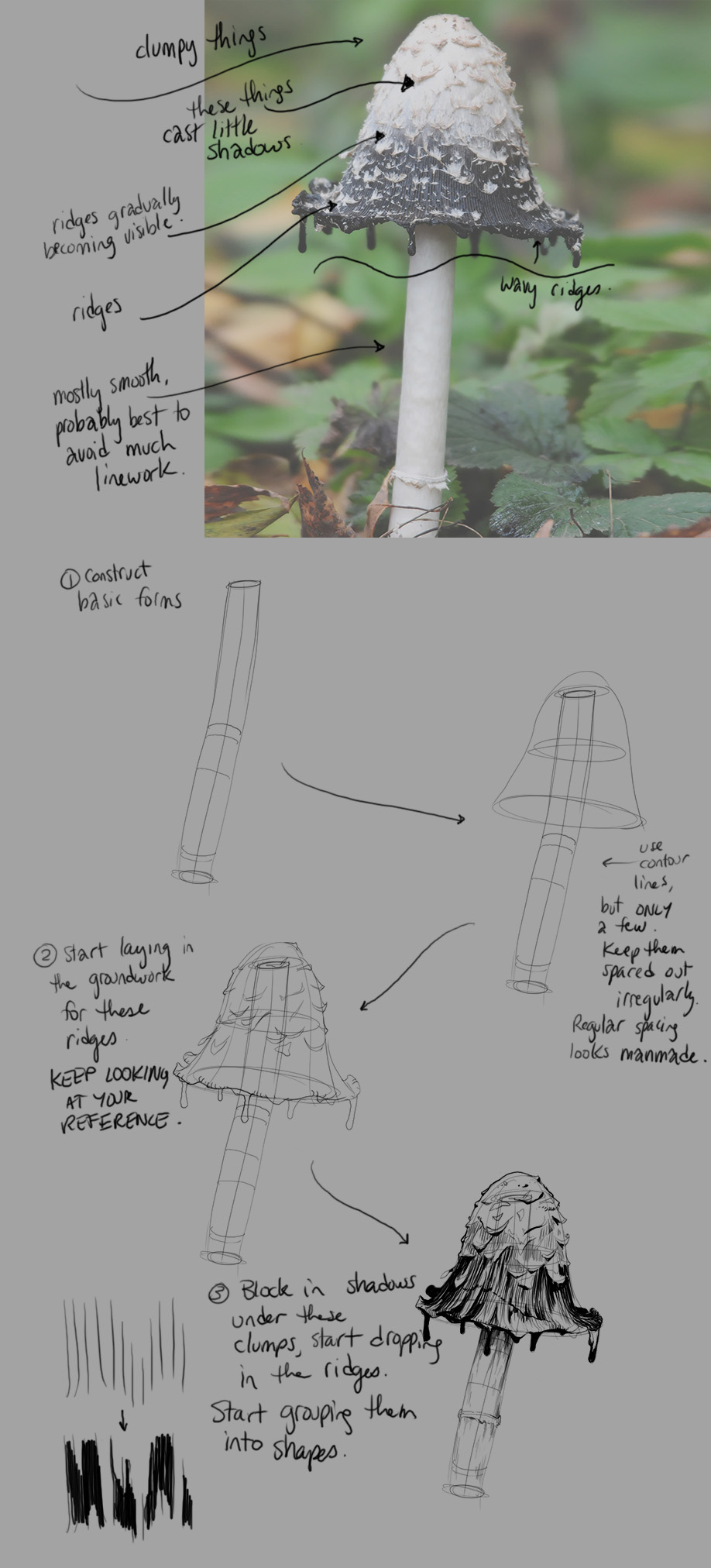

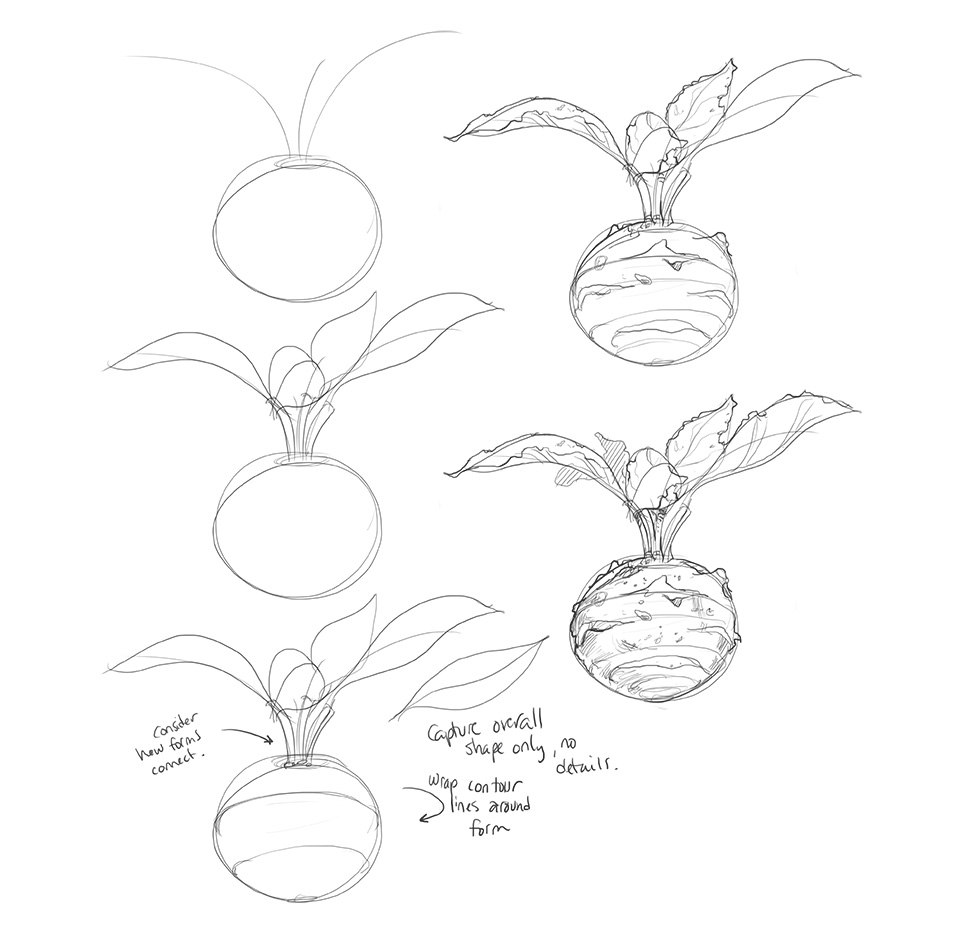

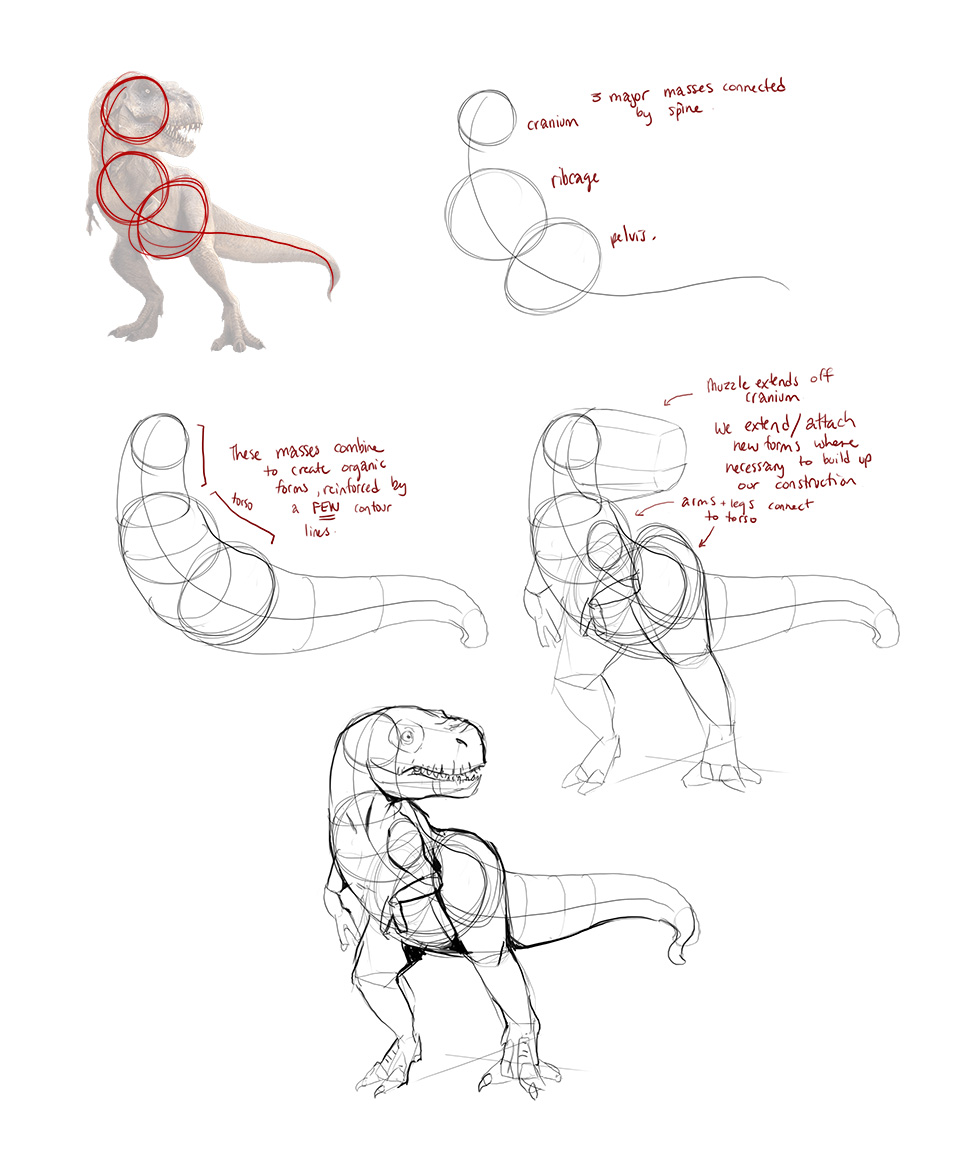

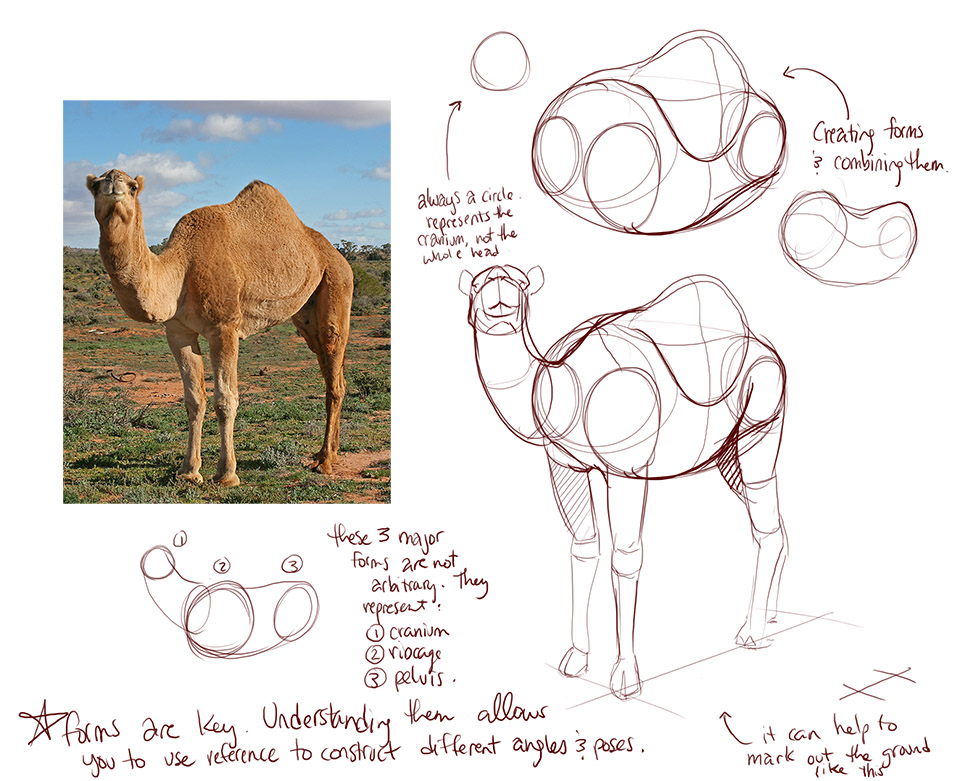

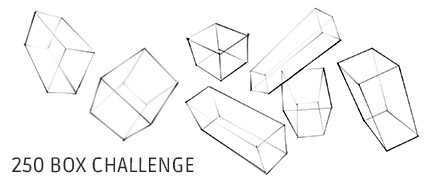

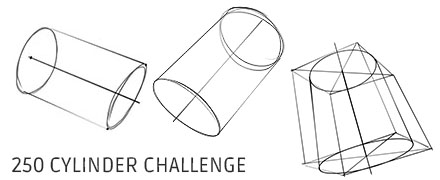

- Observe your subject, whether it's from life or a photograph. Don't focus on the detail, instead try and strip it away in your mind and identify the basic forms that exist. First look for geometric forms, like boxes, cylinders, etc. Next look for organic forms - sausages, ball-like masses, etc (these are still relatively simple). Last of all, look for flat forms - think about the ribbon/arrows from lesson 2, which are flat, but twist and turn in 3D space.

- Identify your subject's basic construction. Think about how all of the components in the previous step relate to each other in 3D space. Think about where they connect to one another, how they intersect, and generally how they come together to create the structure of your object.

- Rebuild this construction on the page. In the first two lessons and the box/cylinder challenge, we look at how to draw the basic building blocks, and how to rotate them arbitrarily in 3D space. Using this knowledge, construct what you've identified in the previous step in your drawing. Remember that you're not drawing the object right now, you're drawing a construction. Ignore detail, ignore complexity, just focus on that simple construction.

- In successive passes, build up the level of complexity. You have a basic construction down - this serves as the foundation for more forms and more complexity. Any additional forms you add to your drawing must be supported by what is already there. I like to think of it like a building. You don't immediately jump in and pile up your bricks til you reach the sky, you build a foundation, then the load-bearing supports, then you create a scaffolding, and so on. Each one is a new pass where more information is added to the drawing.

The biggest mistake students make is getting caught up in detail, or getting caught up in perfectly replicating their photo reference. While many may disagree with me, I don't feel that 100% accuracy is the priority here - instead, it's about understanding how forms work in 3D space. Accuracy certainly is very valuable, but I strongly insist that an understanding of space and construction is fundamental to being able to communicate visually. After all, that is what we're doing - we're conveying a message through visual means.

At the bottom of this article, I've included a few examples on how this approach can be applied to different kinds of subject matter (these are mostly demos I've done in the past). Before we get to that however, I want to stress that this does not replace the importance of observation - in fact, it relies on it heavily. Keen observational skills help immensely when identifying the underlying constrction, and they also help considerably when breaking capturing and applying texture to a surface. The best way to develop this is through studies from life and from photo reference, applying the methodology over and over.

Last of all, remember: a lay-in is not a rough, approximative sketches to "figure" things out. We are thinking through our problems analytically - we think through every mark we put down, and we (generally) stick to them once they're down. You'll notice in the potted fern below that when I start breaking down the leaves into all the tiny parts, they still extend all the way to the edge of the lay-in.